"Every masterpiece is a work of religious music," insisted Ralph Shapey (1921–2001), one of the most original, fearlessly dynamic, outspoken, and provocative—as well as proudly difficult—composers in the elite pantheon of serious American composers of the second half of the 20th century. "My credo," he was fond of declaring whenever the subject of religious conviction was broached and whenever he was asked how his solid Jewish identity affected his music, "is simple:

- All great art is a miracle.

- The music must speak for itself.

- Great art is a mystery and creates—is—magic.

- That which the mind of mankind can conceive will be done, to paraphrase sentiments in the Talmud.

- A work of art must transcend in order to be art.

- Artist: He [God] filled him with the breath and spirit of God—of the Creative Force—with wisdom, knowledge, discerning insight, and physical knowing, to paraphrase sentiments found in the Torah, in b'reshit (Genesis)."

Expanding on that credo, he would often assert that "listening to the masterpieces of music from any period, it's as if they were written yesterday. How could any human being do these things? This is magic, this is mystery, this is beyond belief."

Although he never concerned himself with functional liturgical music, faith was central to Shapey's artistic commitment on many levels. "Do I write Jewish music? I haven't the slightest idea what kind of music I write. . . . It's a human experience. And Jewish is part of human experience for me because I am a Jew. It all relates to the question of individual faith . . . faith in humanity, faith in existence. I write music that I hope will give my audience a sense of eternity, excitation, and being part of the 'Creative Force' with which we are all involved, to greater or lesser extents. We creators, we artists, are fortunate in having discovered our personal link with the Creative Force."

Shapey was born in Philadelphia to immigrant parents from the Czarist Empire. He began violin lessons at the age of seven and then pursued conducting, becoming the conductor of the Philadelphia National Youth Symphony by the age of sixteen. In 1938 he embarked on composition studies with Stefan Wolpe, but his formal education ended with his graduation from high school. "I don't have a damned [expletive deleted] degree to my name," he often boasted with pride, especially after he had attained the rank of full professor at one of the most intellectually rigorous and prestigious universities in the world. A few chamber and solo pieces date from the late 1940s in New York, but he did not fully reach his stride as a composer until the mid-1950s, by which time he had become deeply impressed by the abstract expressionist movement in art—not least through his associations with art critics and important painters of the period, such as Willem de Kooning and Jack Tworkov. His works from the late 1950s and early 1960s already betray that artistic influence, which manifested itself in his own self-developed system of nontonal harmonic language and in his propensity toward vigorous gestures. Shapey taught nearly three decades at the University of Chicago, where he also founded the Contemporary Chamber Players—an extraordinary ensemble that presented and often premiered some of the most difficult and complex 20th-century music under his baton.

For audiences with clearly defined partialities to traditionally tonal, diatonic, and conventional melodic expression, Shapey's music can pose a fierce challenge; and it has been frequently but simplistically cast under the erroneously monolithic atonal/twelve-tone umbrella. "An assault on the senses" was one reaction to the premiere of one of his most complicated, boisterous, and unabashedly taxing orchestral pieces. But on another level, without compromise to his nontonal or pantonal aesthetic, much of his music has, at the same time, a lyrical quality as well as a romantic sweep, even if it may require a measure of preparation and perhaps repeated hearings to appreciate those aspects. In fact, he acknowledged that the label "radical traditionalist" applied to him by critics was indeed apt. "I am not a twelve-tone composer in the true sense of that term," he explained during a Milken Archive film interview in 1997 for its Oral History Project.

Shapey will be remembered for the prize he did not get—the 1992 Pulitzer Prize in music—for his his Concerto Fantastique (1989–91), a work of more than an hour in length that was commissioned to celebrate the centenaries of both the University of Chicago and the Chicago Symphony- and the international furor the incident generated in the world of the arts.

Among his important Judaically inspired works in addition to Psalm II are The Covenant (1977), for soprano solo and sixteen players; O Jerusalem (1974–75), for soprano and flute; Praise (1962–71), an oratorio for bass baritone solo, double chorus, and chamber ensemble; and Trilogy, based on the biblical Song of Songs (three cycles, 1979–80). Shapey received one of the highly coveted (and monetarily significant) MacArthur Foundation grants—the so-called genius awards—in 1982.

| Title | |

| GOUNOD, C.-F.: Romeo et Juliette (Studio Production, 2002) | |

|

GOUNOD, C.-F.: Romeo et Juliette (Studio Production, 2002)

Composer:

Gounod, Charles-Francois

Artists:

Acquarone, Marcel -- Alagna, Roberto -- Czech Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra -- Gheorghiu, Angela -- Guadagno, Anton -- Harvanek, Zdenek -- Hendrych, Ales -- Kriz, Vratislav -- Kuhn Mixed Choir -- Lipnik, Daniel -- Novak, Pavel -- Svab, Jan

Label/Producer: Digital Classics Distribution |

| VIVALDI, A.: Four Seasons (The) [Ballet] (National Ballet of Canada, 2000) | |

|

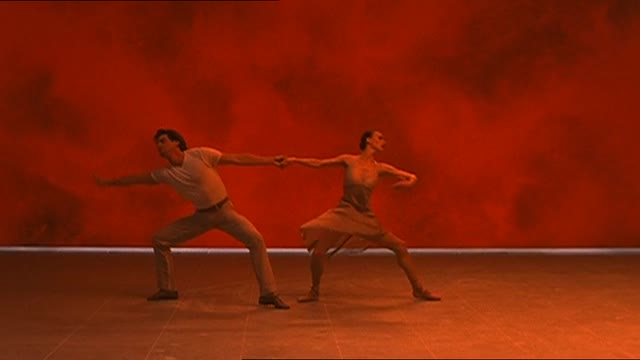

VIVALDI, A.: Four Seasons (The) [Ballet] (National Ballet of Canada, 2000)

Composer:

Vivaldi, Antonio

Artists:

Bertram, Victoria -- Canadian National Arts Centre Orchestra -- Goh, Chan Hon -- Harrington, Rex -- Hodgkinson, Greta -- Lamy, Martine -- National Ballet of Canada -- Ransom, Jeremy -- Zukerman, Pinchas

Label/Producer: EuroArts |